We reach more than 65,000 registered users in Dec!! Register Now

Unlocking the Secrets of Cancer Metastasis: MSK Study Provides New Insights, Potential Therapeutic Opportunities

- December 18, 2024

- 4 Views

- 0 Likes

- 0 Comment

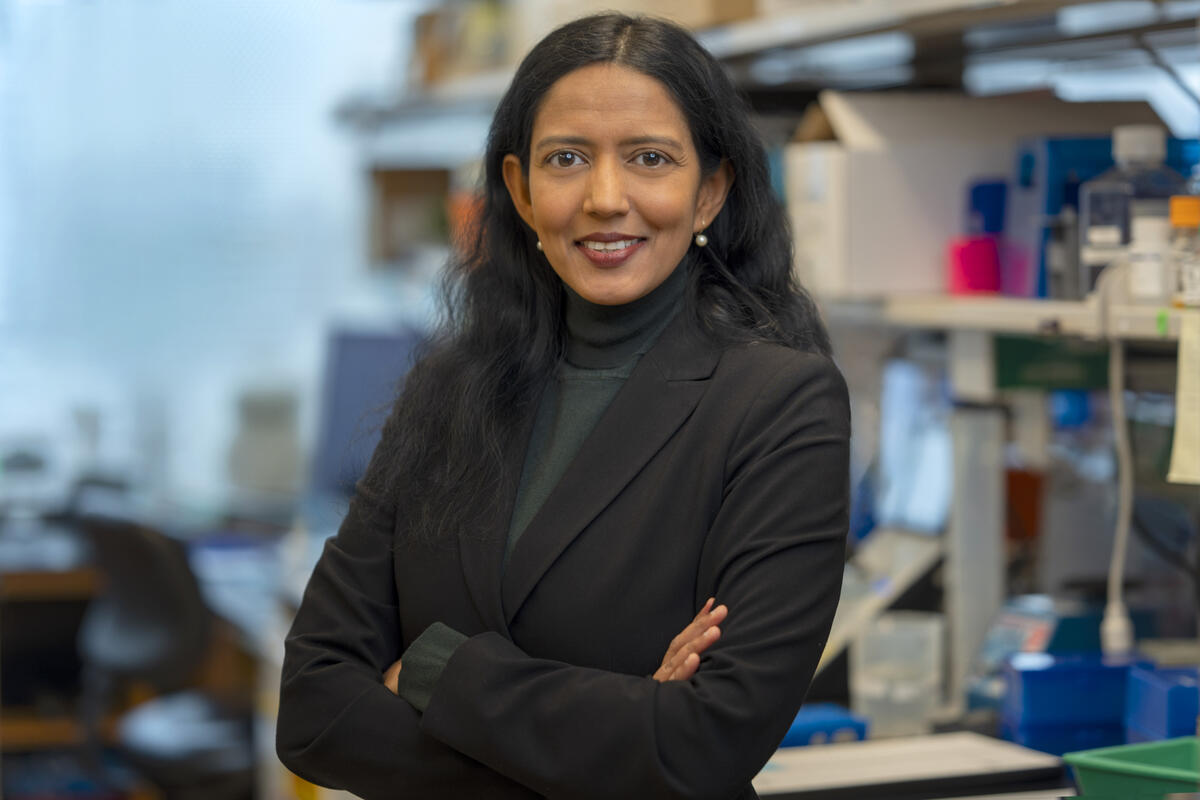

Metastasis remains the primary challenge to reducing cancer deaths worldwide, says Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK) gastrointestinal oncologist Karuna Ganesh, MD, PhD. That’s when a primary tumor — colorectal cancer, for example — spreads to a new part of the body, such as the brain, liver, or bones.

The new tumor is still colorectal cancer (not brain, liver, or bone cancer), yet the cells in the new tumor are also radically different from those in the tumor where the cancer started. And the differences between the two are critical.

Effective treatments against metastasis will require a deeper understanding of both the changes that happen when cells from a primary tumor metastasize and the mechanisms that drive those changes, she adds.

Now a new MSK study, published October 30 in Nature, overseen by Dr. Ganesh and MSK computational biologist Dana Pe’er, PhD, is providing unique insights into metastasis that researchers say point to new therapeutic opportunities.

Study Illuminates Differences Between Primary and Metastatic Colorectal Cancer

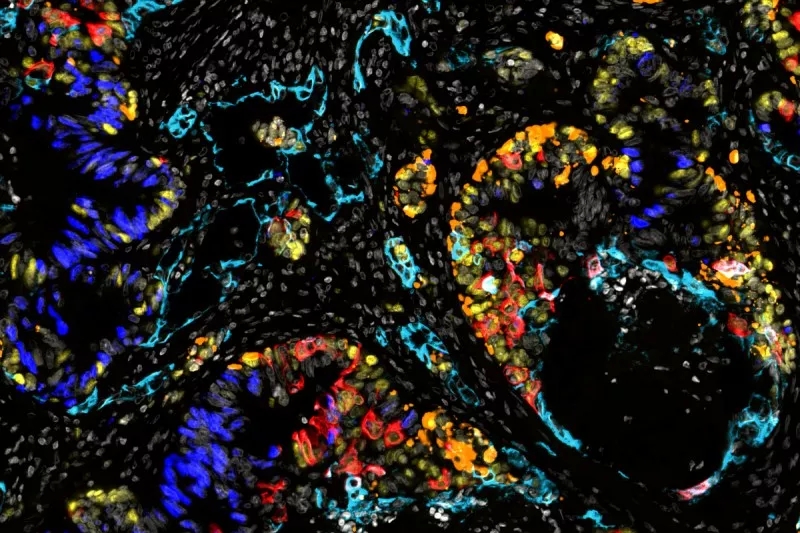

The scientists’ findings provide new details about metastatic cancer cells’ ability to “time travel” back to earlier, flexible states seen in embryonic development — what scientists call “cellular plasticity.”Plasticity refers to the ability of cancer cells to shed their identity as, say, intestinal cells and to return to a primordial state that can give rise to completely different cell types: skin-like cells (squamous), bone-like cells (osteoblasts), and cells that release hormones and communicate with the nervous system (neuroendocrine).

By comparing samples from patients with advanced colorectal cancer, the research team identified clear patterns in the way metastatic cells reprogram themselves to access these early cell states.

The effort required innovative thinking, sophisticated experimental and computational expertise, and extensive collaboration between oncologists, surgeons, and laboratory researchers with a variety of specializations — enabled by the breadth and depth of expertise at MSK, the collaborative culture, and the volume and nature of the cases that MSK researches see, the researchers say.

The study was led by co-first authors Andrew Moorman, MS, a computational biologist in the Pe’er Lab, and Tri-Institutional MD/PhD student Elizabeth Benitez and postdoctoral fellow Francesco Cambuli, PhD, both from the Ganesh Lab.

Back to top

Studying Metastasis Using Three Kinds of Tissue

The researchers collected a trio of samples from each of 31 patients — from their primary tumor, nearby healthy tissue, and metastatic tissue (usually from the liver).The researchers then used single-cell RNA sequencing, advanced immunofluorescence microscopy, and organoids (miniature lab-grown model organs) generated from the samples to study the cancer cells’ evolution during metastasis.

The study included patients who had not yet received any cancer treatment, as well as those who had received chemotherapy before surgery. Some patients had additional samples collected at a later time.

Analyzing matched trios of tissue from a group of patients is an innovative way to get insights into one of cancer’s biggest challenges. Standard laboratory models, such as cell lines or mice, can’t readily answer key questions about why metastasis gains such aggressive capabilities that eventually kill, which primary tumors alone usually don’t, the researchers say.

Mouse models of cancer often don’t metastasize, and when they do, the process is greatly accelerated compared with how cancer evolves in people — which means they’re not particularly accurate for understanding the development of plasticity in human cancers on human timescales, Dr. Pe’er says.

“We thought it was really important to look at the disease for which we need better treatments, which is advanced cancer in humans,” Dr. Ganesh says. “So we had to get a little creative, because when patients get metastatic disease, we don’t often perform surgeries to cut it out.”

Moreover, surgery is a very specialized field. Surgeons do sometimes take out part of the liver to remove a metastasis, but generally a different surgeon would operate on the colon to remove a primary tumor.

“So we really had to bring together a broad, collaborative group to collect and study these different samples during one surgery,” Dr. Ganesh adds. “What we’ve been able to achieve — to be able to look at normal tissue, primary tumor, and metastasis from the same patients at the same timepoint — has never been done at this scale before.”

List of Referenes

- A. R. Moorman, E. K. Benitez, F. Cambuli, Q. Jiang, A. Mahmoud, M. Lumish, S. Hartner, S. Balkaran, J. Bermeo, S. Asawa, C. Firat, A. Saxena, F. Wu, A. Luthra, C. Burdziak, Y. Xie, V. Sgambati, K. Luckett, Y. Li, Z. Yi, I. Masilionis, K. Soares, E. Pappou, R. Yaeger, P. Kingham, W. Jarnagin, P. Paty, M. R. Weiser, L. Mazutis, M. D’Angelica, J. Shia, J. Garcia-Aguilar, T. Nawy, T. J. Hollmann, R. Chaligné, F. Sanchez-Vega, R. Sharma, D. Pe’er, K. Ganesh. Progressive plasticity during colorectal cancer metastasis. Nature, 2024; DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-08150-0

Cite This Article as

No tags found for this post